Worlds

in motion

Worlds in motion

Worlds in motion, tells different stories of human and non-human mobility in the present world of the Anthropocene. The different interventions paint a comprehensive picture of the complex socio-ecological factors behind increased mobility in the spaces in which planetary change meets the lived realities of local populations, like cities, small island developing states, and indigenous communities. Together, they demonstrate that in the Anthropocene epoch movement and mobility represent the norm and not the exception.

U.S. Immigration Policy, Environmental Racism, and Concentration Camps

by David Naguib Pellow

In recent years, the U.S. border has increasingly become a site of conflict over a perceived crisis in the number of immigrant crossings from Mexico and Central America. The real crisis is, of course, the denial of human rights, but I would suggest that there are other, critical framings of this story that need to be addressed, that allow us to link state violence to environmental racism impacting people who seeking a better life. Environmental racism is the disproportionate exposure to negative environmental health risks that marginalized communities face everyday. This phenomenon is amplified by the restricted mobilities that low-income, people of color, and undocumented populations confront on a routine basis when seeking to cross social and geographic borders to improve their life chances and escape violent circumstances. Restrictions on mobility for marginalized peoples also reflects the power of social privilege among elites, who desire to control the movements of undesirable groups in order to also maintain their own status and access to exclusive environments.

These tensions have made news headlines in recent weeks. Congressperson Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez described the migrant detention prisons holding asylum seekers in deplorable, squalid conditions as “concentration camps.” Predictably, she was roundly criticized for alleged insensitivity to victims and survivors of the Nazi-led Holocaust, but this response stems from a lack of understanding of the terms and a profound ignorance of history and the present, so I would like to clarify those matters here.

The term concentration camp is used to describe imprisonment based on the social category you inhabit, not for any alleged crime you may have committed. Thus, during the Nazi-led Holocaust, when Jews, Slavs, Roma, LGBTQ folk, disabled persons, and persons of African descent were imprisoned, those sites were both concentration campus and “death camps” because they were places where people were imprisoned because of who they are and because their primary purpose was extermination. The U.S. is imprisoning immigrants in concentration camps because they are undocumented persons who are simply seeking asylum. Sadly, the U.S. has a long and shameful history of warehousing people in concentration camps, including, for example, Fort Snelling in Minnesota, which was set up by the U.S. government in the 1860s to neutralize the resistance movement by Dakota peoples who were pushing back against the conquest of their lands. That concentration camp was a site of genocidal mistreatment of the Dakota, resulting in malnutrition, mass starvation and death among hundreds—a profound instance of environmental racism because they were forcibly disallowed from feeding themselves from their traditional land base. The wounds of that era remain with us as Fort Snelling today is a monument to U.S. Empire that thousands of white Minnesotans celebrate every year. During World War II, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued an Executive Order to send thousands of Japanese American citizens to concentration camps in the western U.S. in order to contain the perceived threat that they posed to the nation, since the government suspected many of them to be sympathizers with the Japanese empire (a claim that was proven false). During that time of Japanese American mass incarceration, the prisoners faced serious water contamination because the US military delivered drinking water in the camps through old pipes that had previously been used to store oil and gas. As a result the water was laced with hydrocarbons and toxins, placing the Japanese American prisoners’ health at significant risk. In many other cases—such as the camps at Gila River and Poston, Arizona—numerous prisoners at these sites experienced extreme heat, dehydration, and many stillbirths as a result of the harsh climate and social conditions imposed on them—horrific examples of environmental racism. And all across the United States today, citizens who are people of color are housed in prisons and jails with inadequate medical care, substandard food, and a range of major environmental risks as a result of racist, oppressive, discriminatory policies and practices within labor markets and law enforcement that target, profile, and prey on these populations not because of anything they have done but because of who they are and because of the structural violence perpetrated against them by this nation’s major political and economic institutions. For this reason, many anti-prison activists have long referred to the prison system in the U.S. as a network of concentration camps as well because the vast majority of people languishing inside are there primarily because they are poor and people of color and have been criminalized since birth.

The flipside and driving force behind environmental racism is the quest for environmental privilege, which is the practice of producing coveted, exclusive access to cleaner, healthier land, water, air, and space, which elites, the affluent, and powerful can secure while the socially marginalized cannot. Thus environmental privilege is a social force that restricts the mobility of some populations and enhances the unjust and largely unrestricted mobilities of others. Environmental privilege results in segregated neighborhoods and residential communities but it also supports and reinforces the militarization of national borders and the construction of prisons. Thus what many people typically think of as “immigration” policy often has strong ecological and environmental justice implications.

So we should not be surprised that the U.S. has constructed concentration camps for non-citizens who some view as a threat to white supremacy, and we should use this language to communicate the urgency of the situation and the depths of racism and depravity involved. It is imperative that we frame these issues as such in order to more effectively organize in support of human rights, mobility justice, and environmental justice.

Image gallery credits from left to right:

"An 1863 photograph Dakota tipis in the bottomlands of Fort Snelling’s concentration camp," courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society"Angola State Prison in Mississippi," by Oliver Geer

"Families detained at the US Border Patrol McAllen Station on June 10, 2019 in McAllen, Texas," by Office of Inspector General, US Dept of Homeland Security via Getty Images, June 2019

“Japanese Americans behind barbed wire in a camp in Santa Ana, California,” Warfare History Network

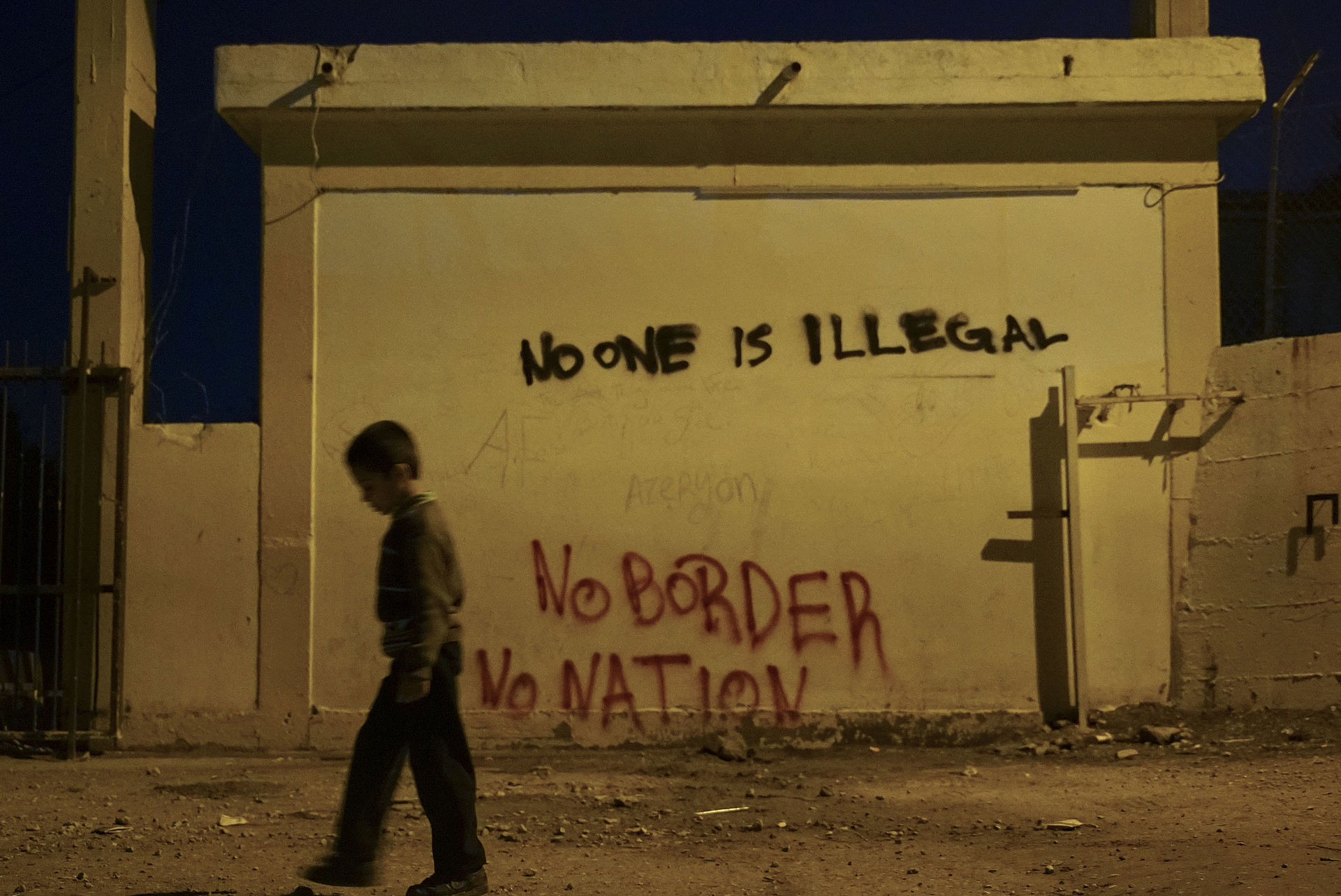

“Underaged refugee in a camp on the Greek island of Lesbos, 30 January 2016”, Wikimedia Commons

Commoning urban citizenship

by Ethemcan Turhan and Marco Armiero

On 29th June 2019, captain Carol Rackete of Sea Watch 3 took a bold decision to move her ship towards Lampedusa port despite repeated warnings of arrest and harassment from the top echelons of the Italian state. After 16 days aboard the ship, 40 migrants saved from death before the eyes of the whole world finally touched European territory. Arrested immediately at this port of call, Rackete made a simple but very powerful statement “I am white, German, born in a rich country and with the right passport. […] When I realized it, I felt a moral obligation to help those who did not have the same opportunities as me.” Hailing from the neo-fascist trenches, Italian minister of Interior Salvini was quick to respond: “Lampedusa and Italy need tourists who pay, not illegal immigrants whom we must support.” Lampedusa itself is a deadly name in the Mediterranean, which witnessed one of the biggest tragedies when more than 360 people drowned in a capsized boat in October 2013. Salvini similarly is a deadly name whose December 2018 decree created tens of thousands of urban homeless after abolishing humanitarian protection for those not eligible for refugee status in Italian cities. This overlap, we argue, is not coincidental. It is the part of ongoing efforts to bring back and embolden the isolationist fortress models for the privileged few and commodify our cities.

In our recent piece in Mobilities, we argue for a counter-hegemonic strategy to build urban citizenship as mobile commons. Cities emerge as the junctions where mobile populations meet the abrupt and concentrated manifestations of climate change and resource constraints as well as facing the intermesh of austerity, authoritarian populism and their xenophobic residues. Rather than accepting the immobile forms of citizenship as the norm, we argue urban space matters in responding to intertwined challenges of climate change and human mobility. Similarly, power matters in responding to exclusionary forms of responses to these challenges and radical grassroots actions matter as contingent possibilities of reframing the urban citizenship as mobile commons. Building on mobility justice and climate justice, we suggest that such reframing inevitably encompasses both new scalar imaginations and a solid, material right to the city. Going against the grain of territorially bounded notions of citizenship, we argue that the Anthropocene calls for a radically different urban reality that is open and unfixed for all. While the far-right wing nationalists propose a cheap notion of citizenship, where belonging is more a matter of identity against some “others” rather than of positive rights, the urban notion of citizenship is the opposite of such sedentary identity because it fosters a community of diverse people who nonetheless share a collective space and a political project.

Commoning urban citizenship, therefore, becomes a political strategy to push for such a power shift to enact spatial and social transformations in making mobility the norm and not the exception. We believe that the power of urban citizenship as mobile commons lies at the very possibilities it can trigger in disenfranchising the physical, political, economic and social borders within and between nation states. Addressing Anthropocene mobilities require no less than such a bold shift in citizenship and with this call for a bold shift, we cannot but turn to the yet open question Gramsci once posed: “How can the present be welded to the future, so that while satisfying the urgent necessities of the one we may work effectively to create and ‘anticipate’ the other?”